AI-powered robots learn to stand on their own two feet

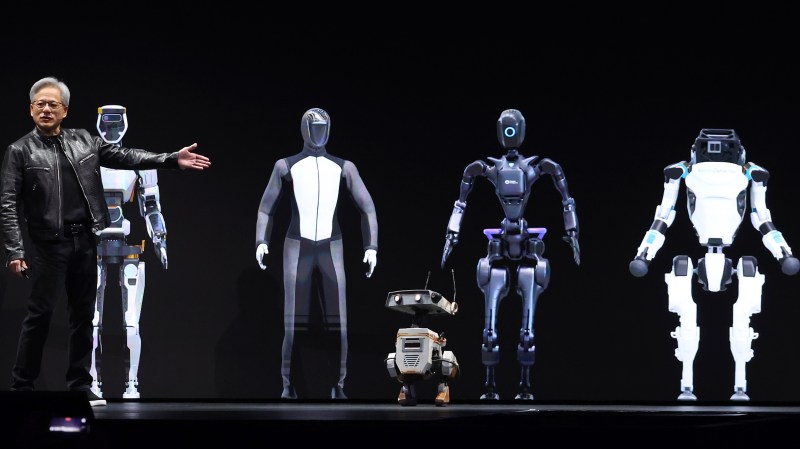

A green, knee-high robot shuffled to the stage at the San Jose Convention Center to cheers from an adoring crowd of nerds. Jensen Huang, founder of AI chip-maker Nvidia and one of the richest men in the world — net worth $80 billion — beckoned the little droid closer.

“Come here, Green,” he said. “Stop wasting time.” Green didn’t move. Orange, an identical robot that had also ambled on stage, was more co-operative. It clomped over and stopped at Huang’s command.

Green’s apparent intransigence was a small fly in the ointment at the showcase conference of Huang’s $2.2 trillion chip giant. But his enthusiasm for this fantastical future was undimmed. It is a future where bipedal, humanoid robots are moments away from bursting onto the world, powered by a novel robotic operating system Nvidia has developed. “Everything that moves in the future will be robotic,” he enthused. “It won’t just be you.” Indeed, before Green and Orange showed up, Huang strode on stage in front of a row of stationary humanoid robots, like a drill sergeant surveying his new recruits.

Since OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT, the chatbot that wowed the world 18 months ago, investors have ploughed an estimated $100 billion into artificial intelligence (AI) start-ups. The AI age, it appears, has begun. But while the world has been transfixed by chatbots and tools that transform text prompts into jaw-dropping videos, a frenzy over robots powered by AI “brains” has taken hold that insiders claim is about to shock the world all over again.

“There are more than 30 companies that I’m aware of that are developing humanoid robots with plans to commercialise in the next year,” Andra Keay, an investor and managing director of trade group Silicon Valley Robotics. She compared their arrival to other world-altering inventions: “Humanoid robots are the automobiles of the 21st century.”

Doubters will guffaw at the idea that droids will soon flood into factories, fast-food kitchens and our homes. Two years ago, Elon Musk announced that Optimus, the humanoid robot being developed by Tesla, would be, “bigger than the car business”. In the event, Optimus ended up being a human dressed in a robot bodysuit who danced on stage.

Green’s on-stage glitch last week could easily be painted as yet another example of why robots are still a very long way from being useful. And yet, a growing number of investors are making huge bets that leaps in AI systems and plummeting component costs are converging with an acute labour shortage and rising wages for human workers to create the ideal conditions for the robots to finally arrive.

Figure AI, a two-year-old Sunnyvale, California start-up, raised $675m this month to commercialise its bipedal bot. Founder Brett Adcock, who previously set up flying-car company Archer Aviation, predicted that human labour would soon be automated away entirely. “We are in the early stages of an AI and robotics revolution. Everywhere from factories to farmland, the cost of labour will decrease until it becomes equivalent to the price of renting a robot, facilitating a long-term, holistic reduction in costs. Over time, humans could leave the loop altogether as robots become capable of building other robots,” he said. “We have the potential to alter the course of history and fundamentally improve millions of lives.”

For years, companies have had to painstakingly train their robots to carry out discrete tasks such as picking up an object and setting it on a table. Ask that robot to, say, grab a hairbrush, or walk across a warehouse, and they are useless. Breakthroughs in AI, however, have led to AI-based reasoning models that are better at understanding the world around them, comprehending what is asked of them, and responding accordingly.

Pras Velagapudi, chief architect of Agility Robotics, a developer of a bipedal warehouse robot called Digit, said: “The newest AI models are very promising in solving some of the upcoming problems that we had anticipated would take years or decades to solve. We’re going to see these types of robots out in the world much faster than we originally anticipated.”

Predictions of mass automation have been made countless times, only to fizzle. And there is something almost cartoonish about robots that are made to look and move like humans. It calls to mind the famed quote about the automobile from Henry Ford: “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

But there are good reasons to try to replicate humans. American warehouse and manufacturing companies have more than 600,000 unfilled positions. Despite the need, many have been reticent about automation because it often requires remaking an operation from the ground up to make an environment suitable for even a modicum of additional automated work.

Therein lies the allure of humanoid robots. Because they are facsimiles of humans in size, shape and locomotion, no complex retrofit is required. A capable droid can, theoretically, be dropped into an existing operation.

A cursory scan of YouTube for demo videos might lead one to think that the robot age is already here. Figure posted a demo of its bot, powered by OpenAI’s language model, that displayed an impressive ability to understand the world around it. When asked for something to eat, it handed its interlocutor an apple. It also appeared dextrous, complying with voice commands to pick up rubbish and stack (plastic) dishes in a drying rack. Tesla published a video in December of the latest iteration of Optimus, which could walk 30 per cent faster than the previous model. China’s Unitree has shown its bots running and climbing up and down stairs.

Dwight Klappich, an analyst at tech consultancy Gartner, is more circumspect. The path from a whizzy video to a truly capable robot capable of operating in the real world, and all the variables it presents, is very long indeed. “Over the next 20 years, you’ll go into a McDonald’s and it’s going to look like Star Wars. There will be robots doing a lot of the work.”

Huang, Musk and the rest are betting that future will arrive far faster.